Consent Is Pining for the Fjords (Consent Is Dead part 1)

Or has it "ceased to be"?

In my keynote at the recent EIC conference, I contended that consent is dead.

Before you sic the nearest DPO on me, hear me out. My aim was to stir a thoughtful discussion about the future of digital autonomy and personal data control. I believe the whole notion of user-centric permissions needs a radical makeover if we want it to align with both our privacy ambitions and the harsh realities of data monetization ecosystems.

It’s time to ditch the checkbox charade and get serious about fixes. For a start, let’s reality-check the beliefs that underlie our current consent regulations and technologies.

Reality Check: Manifestation of Consent

To be legally binding, consent needs three features. An act or manifestation of consent is the first – we usually experience this as an “I Agree” button or similar.

We tell ourselves… We can force data-hungry companies to sip data through a straw.

We’ve applied massive and expensive efforts to limit the reach of personal data across the globe, including six solid years of GDPR enforcement and fines. Consent requirements have been specified in ever greater detail. And we all spend more time than ever indicating whether or not we agree to personal data collection, use, and sharing.

Reality check: Despite it all, the identity resolution industry can identify every one of us in a heartbeat.

Identity resolution is vastly different from IAM:

It’s indirect. It's typically handled on the back end by aggregation data processors and other third parties with no direct user relationship.

It’s heuristic. It's probabilistic in nature, rather than deterministic, unlike our preferred methods for identity verification and authentication.

It uses Big Data. It uses massive aggregated data lakes and identity graphs to create a 360-degree view of each consumer.

In my experience, few IAM practitioners seem to be aware of this other “identity” industry. It serves as a companion to customer data platforms, feeding them answers about who correlates with whom in a unified way to support targeted advertising.

One company in the space, LiveRamp, achieves approximately 100% coverage of the global online population – yes, very much including the EU – by leveraging cross-links between a myriad of huge data graphs. A newer effort in the space, Unified ID 2.0, adds OpenID Connect but does little to change the picture.

The reality is brutally clear. Whether or not people are actually manifesting consent for personal data use in any one case – and I know some of you privacy nerds, like me, take a “default-deny” approach to every request for consent – the identity resolution ecosystem makes sure our every digital move is trackable and accessible to third parties.

So: It’s time to rethink our belief that we can force companies dependent on data monetization to ingest data in little tiny sips.

Reality Check: Knowledgeable Consent

The second feature required for consent to be legally binding is knowledge. The aim is to ensure we’re sufficiently informed about what we’re agreeing to.

We tell ourselves… We can prevent identity correlation.

It does seem logical. If all that data is being used so heavily to market to consumers, can’t we just stop sharing so much in the first place? Self-sovereign identity solutions even offer cryptographic methods like Zero Knowledge Proofs to help individuals practice selective disclosure in a technically enforceable way. And of course User-Managed Access has selective sharing at its core.

Reality check: Unfortunately, re-identification is typically a simple operation away, even in the presence of sparsely shared data.

A profiling attack can successfully re-identify as many as 52% of anonymized social graph members, using only a 2-hop interaction graph and auxiliary data such as the time, duration, and type of a user’s interaction with a system – metadata that’s effectively impossible not to share.

Anonymization is a big part of the problem. The conventional technique used is k-anonymity, where a data set is transformed to remove specificity. Although k-anonymized data is treated and regulated as if it were no longer personal data, it’s very easy to crack. Wikipedia says “The guarantees provided by k-anonymity are aspirational, not mathematical.” Ahem.

Dr. Sam Smith, creator of KERI, argues that using k-anonymity constitutes privacy-washing. What’s more, he levels a serious charge against privacy protections over user-chosen selective disclosure and the use of ZKP.

The selective disclosure, whether via Zero-Knowledge-Proof (ZKP) or not, of any 1st party data disclosed to a 2nd party may be potentially trivially exploitably correlatable via…re-identification correlation techniques ….

[S]elective disclosure is a naive form of K-anonymity performed by the discloser (presenter). The discloser is attempting to de-identify their own data. Unfortunately, such naive de-identified disclosure is not performed with any statistical insight into the ability of the verifier (receiver) to re-identify the selectively disclosed attributes[.]

– Sustainable Privacy, Samuel M. Smith, September 15, 2023

Read the whole thing. What’s worse, selective disclosure contexts give a false impression of data safety and privacy while encouraging the sharing of verifiably true information. It’s a double whammy, and the individual has little chance of understanding – being knowledgeable about – the exhaust data they are giving away for free, making re-identification easy.

So: Using conventional techniques, nope, we can’t prevent identity correlation. Even using more effective anonymity techniques such as differential privacy and synthetic data privacy is not without its perils, according to Dr. Smith.

Reality Check: Voluntary Consent

The third feature required for consent to be legally binding is voluntariness. (I would have said “volition,” but then IANAL.) We have to be truly willing. A manifestation of consent without either knowledge or voluntariness is considered defective.

We tell ourselves… We can empower people by asking them something at the point of service.

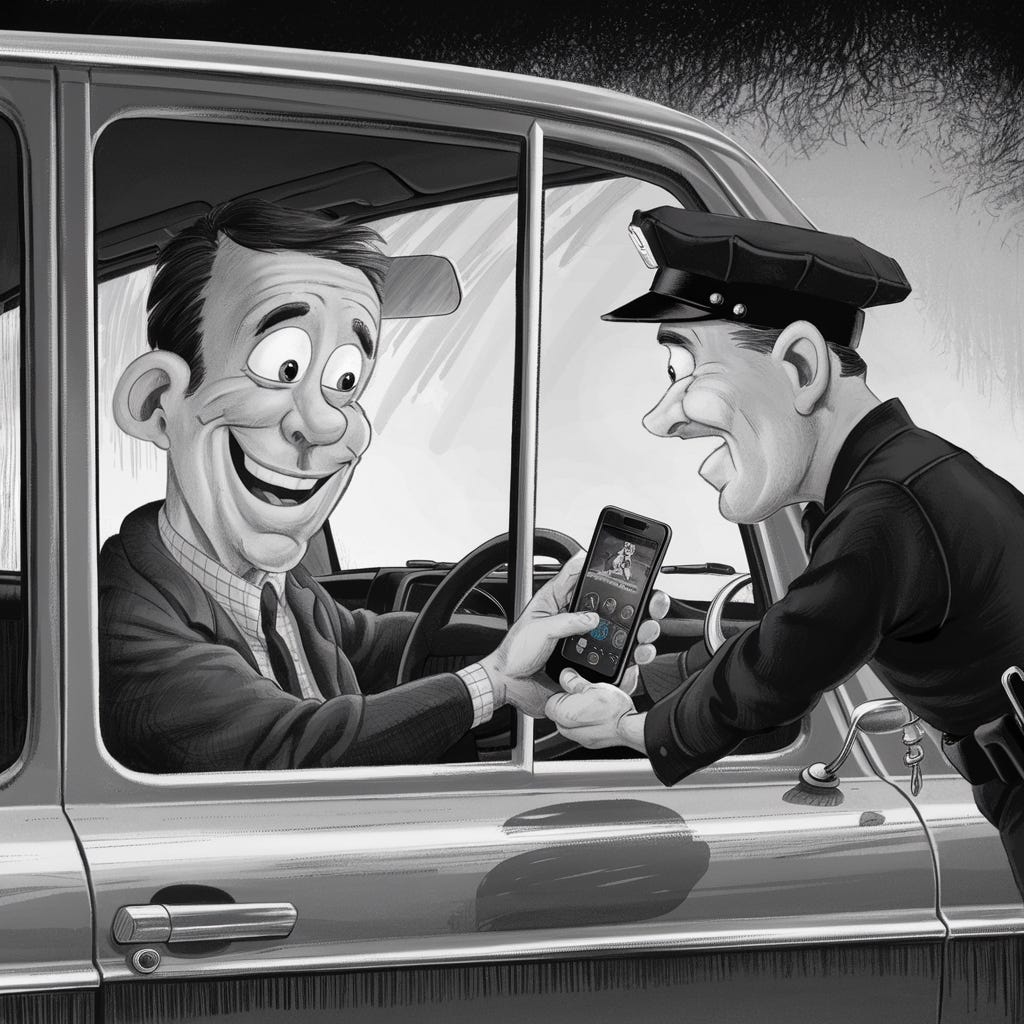

Reality check: If some random person asked you to unlock your password-protected smartphone and hand it over for them to search through while you waited in another room, what would you do? (Warning, AI image ahead, hand/arm confusion and all.)

The “Voluntariness of Voluntary Consent” study found that 97% of test subjects actually went and did it. You may have the best of intentions, but when someone is requesting access, we’re programmed to want to comply. Now imagine it’s a police officer asking for not just your mobile driver’s license but anything else you may have stored in your phone.

We all probably had this suspicion already. As identity ethicist Nishant Kaushik puts it: When denial of consent means denial of service, do people really have a choice? That’s not even counting the ubiquity of actual deceptive patterns.

There is a structural reason for this. Consent is an asymmetrical legal structure, where the individual is first approached by the consent seeker. When you’re tantalizingly close to getting what you want – whether online or in the real world – the power dynamics are skewed.

Contract is another legal structure, also involving consent, for example when we’re agreeing to terms of service and privacy policies. It’s got a few properties that theoretically improve on plain consent, but in practice we’ve all witnessed the problem with these contracts of adhesion.

Privacy researcher Daniel Solove recently published an indictment of both opt-in and opt-out consent constructions in these contexts as “fictions of consent.”

So: It’s unreasonable to expect to empower people by asking them anything right at the point of service. The asymmetry and coercion baked into these interactions mean people don’t have true choice.

Reality-Based Next Steps

The purpose of a system is what it does. There is after all, no point in claiming that the purpose of a system is to do what it constantly fails to do.

– Cybernetician Stafford Beer

Cheer up! Doesn’t it feel good to collect knowledge about the defects in today’s digital consent systems? It helps us figure out how we can move the needle in creating new systems.

In future posts, I’ll introduce alternative beliefs that could anchor our ambitions to do better, along with cutting-edge technological solutions that could help us live up to those beliefs. Stay tuned!

Now it’s your turn. What’s your experience been, either consenting in real life or implementing consent systems? Where am I getting things wrong? What tech do you propose to solve consent problems? Let me know in the comments, and please join me, along with identity geeks Mike Schwartz and Jeff Lombardo, for episode 33 of Identerati Office Hours on July 25 to discuss and dissect the matter.